EXPLORING LARGE FORMAT

CAPTURING VIDEO FROM AN 8X10 FILM PLANE

PREFACE

While cinema companies currently use the terms “large format” and “full frame” to somewhat vaguely refer to film back sizes larger than super 35, I will be using the term “large format” as it is used in still photography, wherein large format cameras have a film back of 4×5 inches or more.

The following are my attempts at creating something which could capture large format video for cinema purposes.

—

GOALS

Large format photography can have many different visual attributes, not all of which I wanted to capture. In considering visual styles, I like to discuss equally not only what aesthetics I want to achieve, but what I want to explicitly avoid.

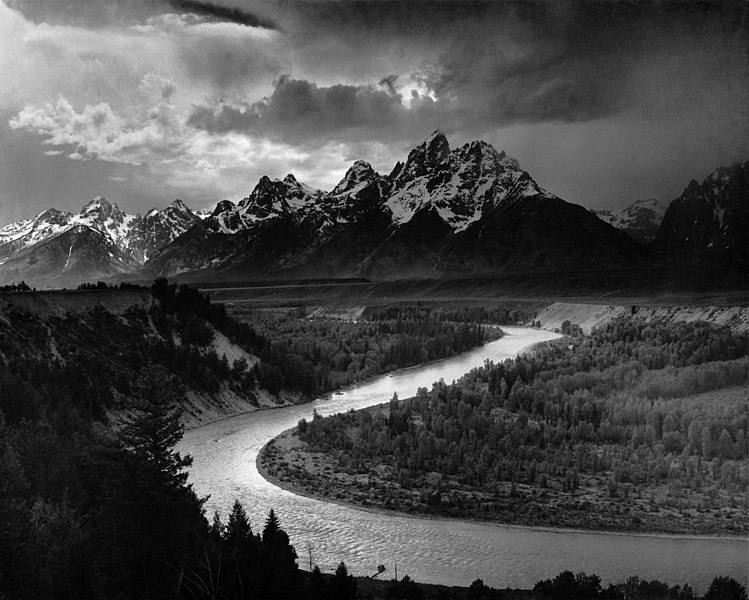

When thinking of period large format, one source that always comes to my mind is Ansel Adams’ photography. A co-founder of Group f/64, Adams seemed to feel strongly about extreme clarity of his images. From their Wikipedia:

Group f/64 or f.64 was a group founded by seven 20th-century San Francisco Bay Area photographers who shared a common photographic style characterized by sharply focused and carefully framed images seen through a particularly Western (U.S.) viewpoint. In part, they formed in opposition to the pictorialist photographic style that had dominated much of the early 20th century, but moreover, they wanted to promote a new modernist aesthetic that was based on precisely exposed images of natural forms and found objects

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Group_f/64

Much of these goals I think can already be achieved using off the shelf methods. The combination of high resolution sensors or film, sharp lenses, and relatively low amounts of noise or grain helps to create the “sharply focused” images that Ansel Adams is famous for.

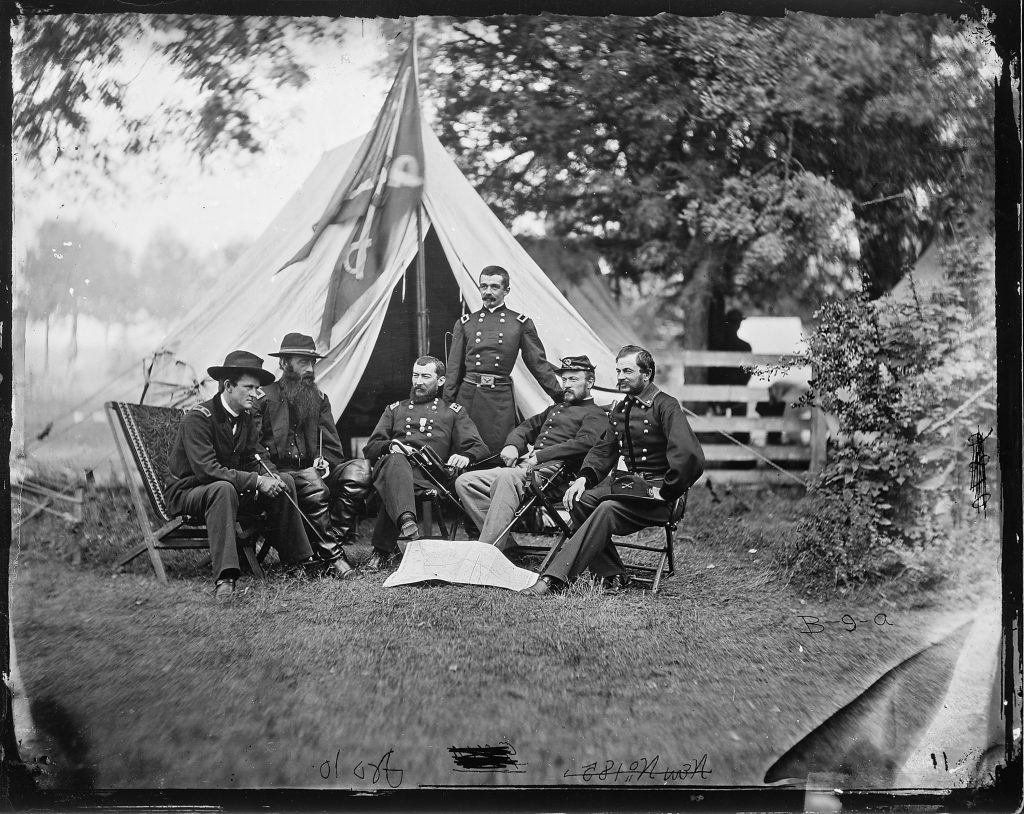

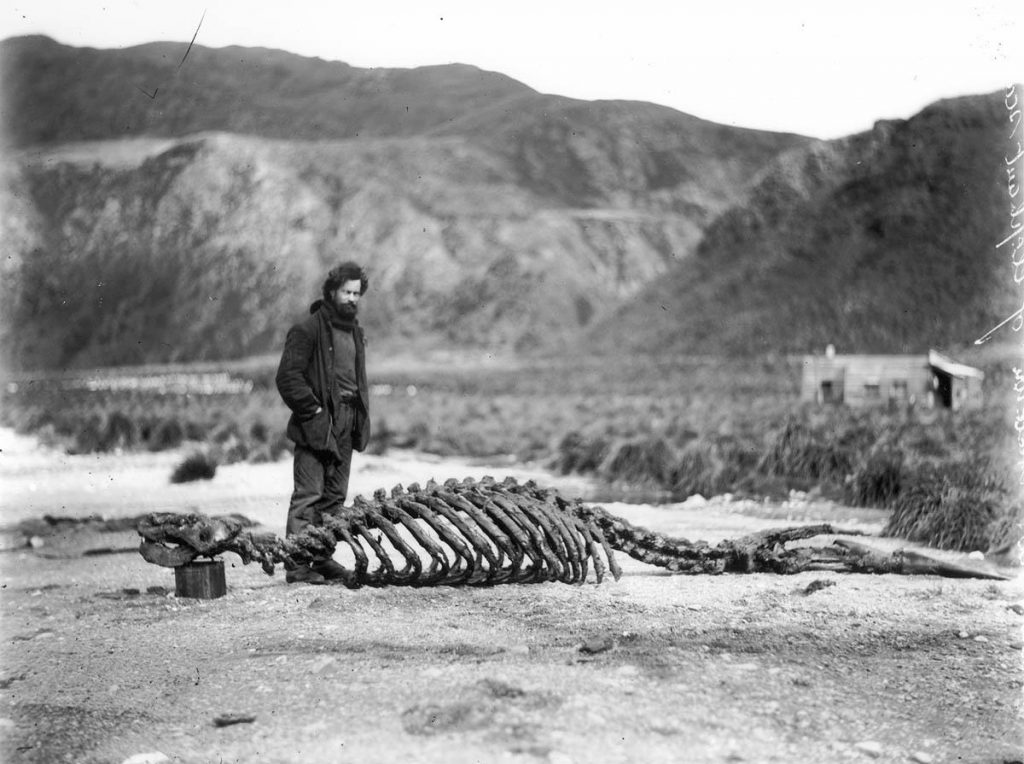

For this experiment, this is specifically not what I wanted to emulate or capture. This research was related to a historically rooted story, so my references skewed strongly toward period photographs, centered mainly around war and exploration. My interests in large format photography can be seen more clearly in the following photos:

We can scrutinize many intriguing visible features, but in an attempt to move forward I will focus on what I think is the most empirical aspect of these period photographs: Depth of Field; and more specifically, shallow depth of field in medium and wide Angles of View.

In reference to the first image, you can see the trees behind the tent are noticeably out of focus, even though the angle of view is not particularly telephoto, nor are the trees especially far from the group. The same can be noticed from the other images.

I’d like to be clear that I don’t necessarily believe this is the most important aspect of large format photography that I’d like to recreate, but this aspect is easy to see and measure, so I’m using it as an origin to judge whether or not the work I am doing can be useful and justified.

—

MATH

The simplest reasoning behind the extremely shallow depth of field seen in period large format and plate photography is based on the size of the film back. To demonstrate the difference in DoF between an 5×7 inch film back and a super 35mm film back, we can use some handy sites to help with the calculations. With a subject 10 feet away, the two formats would have approximately the following DoF while maintaining the same horizontal AoV:

5×7 Film Back with 250mm lens at f/4: ~160 mm

Super 35mm Film Back with 35mm lens at f/4: ~1,320 mm

Or, put another way, the super 35mm lens would need to be set to ~f/0.5 in order to approximate the 5×7’s DoF.

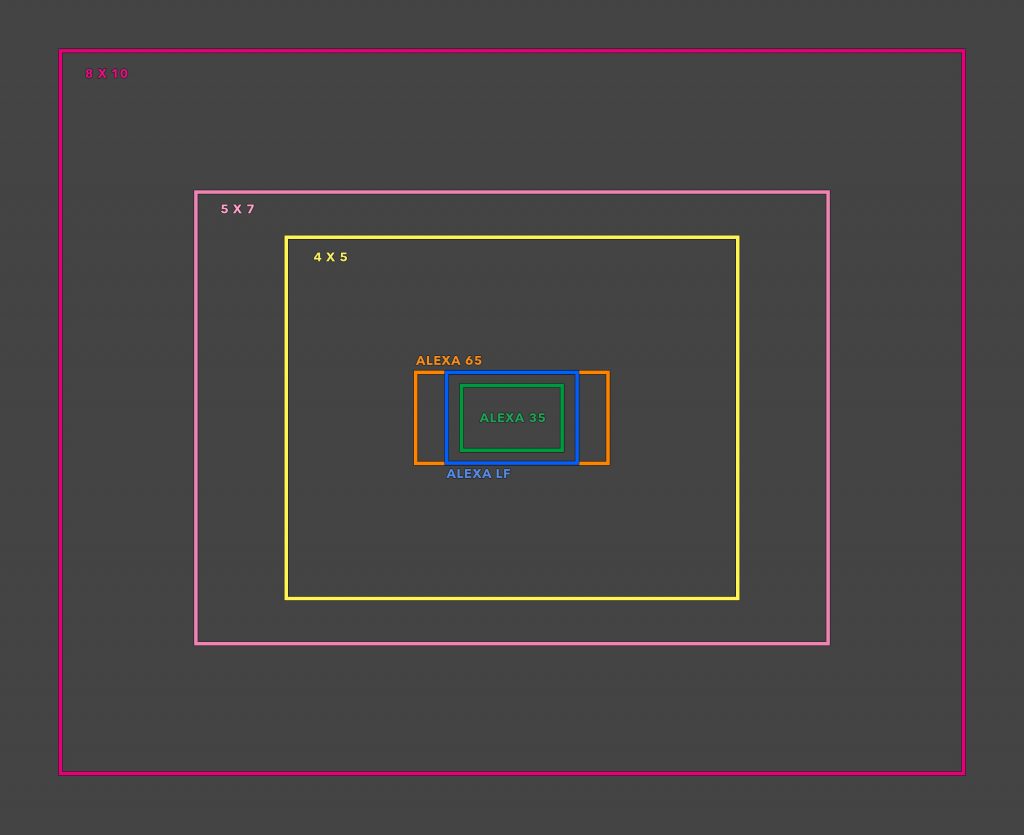

I would like to note that there is currently a commercial option that can achieve DoF close to the example provided: The Alexa 65 with a 75mm lens at f/1.2. Various manufactures provide current cinema lenses somewhat close to these specifications. However, this is only applicable when using the full width of the Alexa 65 sensor, which provides approximately a 2:1 aspect ratio. Matching a taller aspect ratio, a larger film back (such as 8×10), or a wider F stop than f/4 are not even close to possible with current available offerings.

For a clear sense of the physical size difference between large format photography film backs vs current cinema film backs:

—

AVAILABLE SOLUTIONS

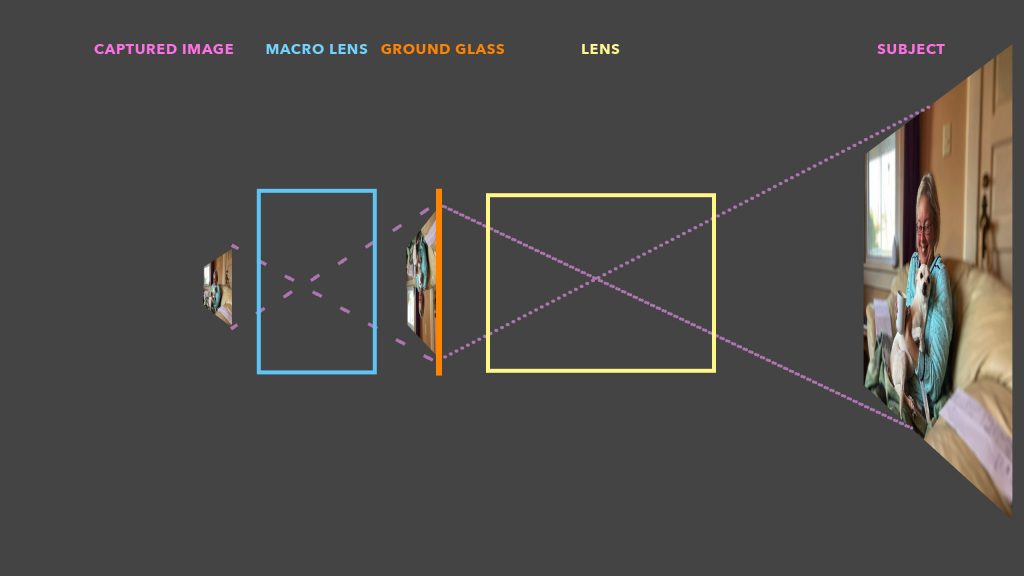

For more than a decade, there have been commercially available methods of “faking” depth of field, generally referred to as a DoF Adapters (wikipedia article). These are not actually faking anything, but rather projecting an image onto an intermittent film back and allowing another camera to record that image. In its basic form, the subject is projected onto ground glass, then the ground glass is recorded using a macro lens attached to the recording camera.

Without correction, this method introduces decreased resolution and significant falloff, especially from wide lenses due to light scatter. The effect produces significant vignetting in the image, making wide lenses unusable.

This can be corrected with additional lens elements: refocusing the light back toward the taking sensor. As this concept is scaled up, the corrective glass necessary could have the potential to create the need for a massive piece of corrective glass, but this problem was solved long ago with the invention of the Fresnel lens.

This concept was successfully executed and documented by two folks who both came up with some really creative solutions to some additional issues. I highly suggest checking them both out, as they also go over some of the issues I mention above in much more detail:

Building a Next-Level Camera – DIY Perks

Building a Large Format DoF Movie Camera – Media Division

—

AN ALTERNATE CONCEPT

The above solutions all film through the ground glass (and do it very successfully), but I wondered if there was another way to simply record the film back directly and in the process, create a more compact solution. This is of course not a new idea, and has been done before:

LARGE FORMAT VIDEO CAMERA – Zev Hoover

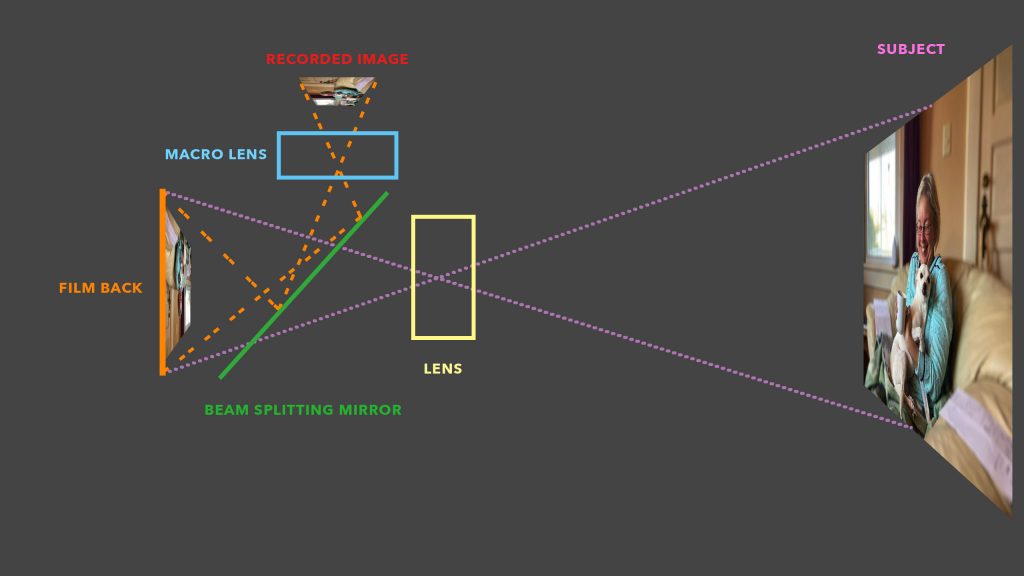

The main limitation with this method is the positioning of the recording camera: even with an extremely wide and heavily shifted lens it seems to still be in an inconvenient location which limits or at least complicates the lens or focusing options. Looking at a beam splitting stereoscopic camera rig, I wondered if this design could be repurposed for my use.

The basic schematic would follow this rough outline:

The main physical restriction would be the height of the film back – as this needs to be matched by the size of the beam splitting mirror, and results in limiting the distance the lens can be from the film back. Thankfully, this is generally not an issue except when focusing to infinity on extremely wide lenses.

—

THE BUILD

Using aluminum extrusion, a beam splitting mirror, a cheap old 250mm lens, and parts from a Horseman large format camera, I ended up with the following:

Which resulted in this image:

Additional tweaking to the design over the next few months led to improved exposure, added wireless focus control and video outputs, and general usability of the rig. Please enjoy these stills pulled from various additional tests I did using this setup:

—

NEXT STEPS

At this point, I consider the largest untested hurdle in making this production ready is further mitigating light loss and the need for an extremely sensitive recording camera. The beam splitter cuts approximately 2 stops of light, with the painted film back’s reflectivity cutting additional exposure,

Additional lens testing is also required, as there are many lenses that have been released for large format cameras over the last century, each with their own unique characteristics.

My current list for further testing and improvements to this rig:

– Testing different materials for the film back. Specifically testing projection materials with a higher screen gain

– Testing additional recording cameras with better high ISO performance

– Testing additional lenses

– Testing additional types of beam splitting glass

There is also the consideration that this rig is not even necessary to capture the aspects of large format that might be the most interesting. Heavily distorted bokeh shapes and focus planes can be found in lenses designed for any format, and seeking out lenses using older design principals can often exhibit beautiful vintage distortion. The Petzval lens design was one of the earliest portrait lenses built, and it’s design has influenced lenses like the vintage Helios 58mm as well as modern cinema lenses; Blackwing states the Petzval design influenced some of their lenses. Arri has recently unveiled a collection of lenses dubbed Heroes, which have tunable bokeh swirl. Options ready for cinema use have grown rapidly recently.

I’d like to wrap this up by returning to the quote from Group f/64:

… photographic style characterized by sharply focused and carefully framed images … based on precisely exposed … natural forms and found objects

As I’d noted before, sharply focused was not an aspect I was looking to replicate in these specific tests. However, careful framing, exposure, contrast, and subject matter can all nod toward the visual styles of this era of photography, regardless of the technology being used.

Stay wonderful,

Zach

—

FURTHER READING

The Cine Lens Manual by Jay Holben and Christopher Probst

DP Steve Yedlin’s site is a wealth of information.

▾ other posts ▾